Measurements made easier

Measuring and then entering distances and angles can be a lot of busywork, which AxoTools Measure tool can help streamline. Just click and drag with the Measure tool. These values are entered into the AxoTools Information panel as measured on your artboard in orthographic projection, as well as the three axonometric planes of your current document projection, plus the depth axis of any currently-defined auxiliary projection.

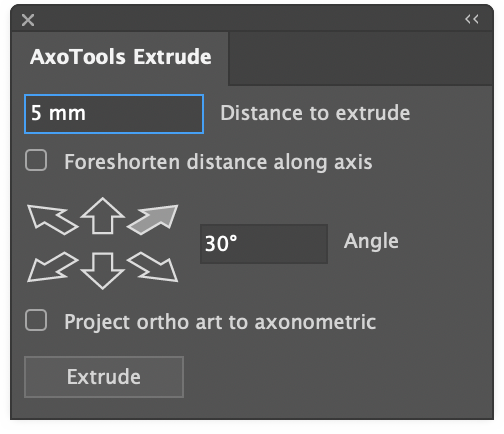

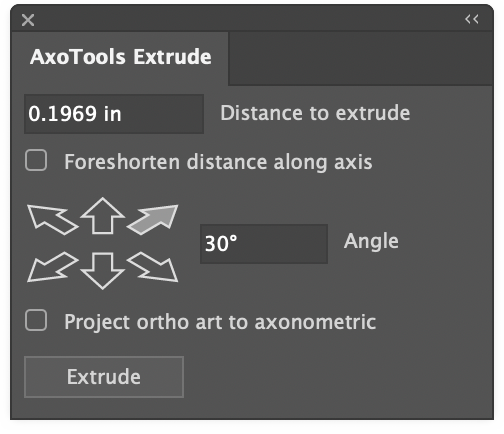

In addition, many of the text fields in AxoTools panels have shortcuts to import values from that panel. For example, you can drag the tool along an edge of an extrude art object to measure its length and angle. Then in the Extrude panel, double-click the Distance and Angle field labels to automatically enter the last-measured values, then simply click the Extrude button. It’s so fast and easy, it almost feels like we’re cheating!

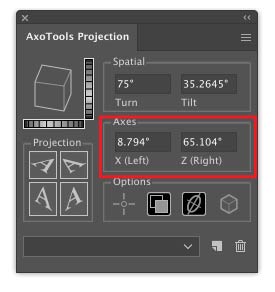

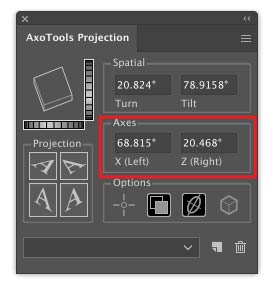

The double-click trick also works for the Projection panel’s X and Z axis fields and the Transformation panel’s Extrude distance field. To auto-enter values into the Transformation’s Move/Rotate field, just type an “a” for angle or “d” for distance as appropriate for your current operation. In the transformation panel’s two fields, you can also type “=” to toggle the value between positive and negative.

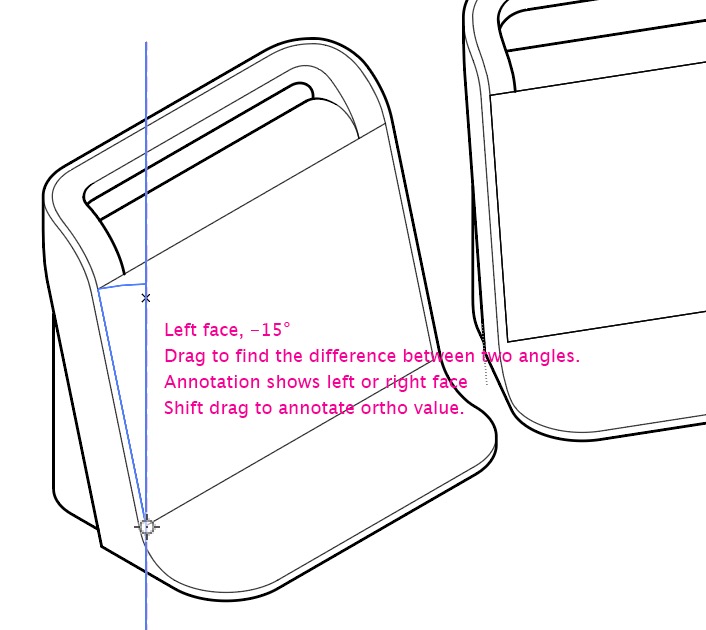

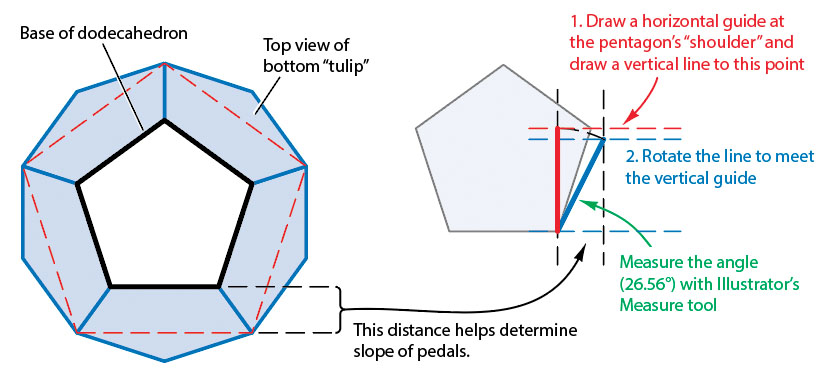

You may want to measure the difference between two angles on an axonometric drawing. Using Illustrator’s built-in Measure tool, you would measure one angle, write down the result, measure another angle, write down that result, then do the math to find the difference, and it would still only be accurate for the flattened view. AxoTools’ Measure tool can work as an axonometric protractor — just click on an anchor point, then drag between two points. You’ll see the corresponding angle from your axonometric plane.

Now you can also now do simple math operations in many of AxoTools’ panels’ fields. For example, you can enter “.25 in + 2mm” and the Extrude panel will calculate the equivalent distance in your current document ruler units (e.g., 23.6693 pt). You can also do math on angles, such as “90 – 32.48” for “57.52°.” Division is done with a “/” character and multiplication with a “*” character.

You can download AxoTools and try it out with 1,000 trial operations. It’s on sale for 1/3 off through May 2022, with annual subscriptions 1/2 off, starting as low as $5!

![]()

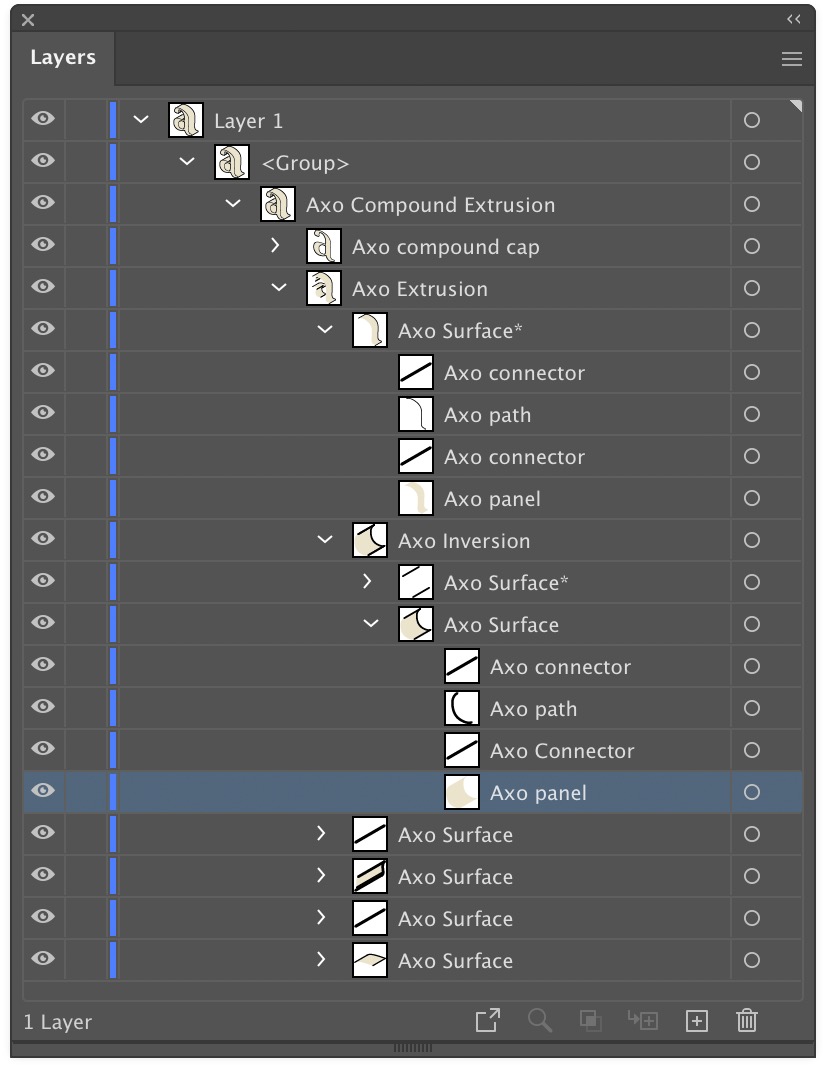

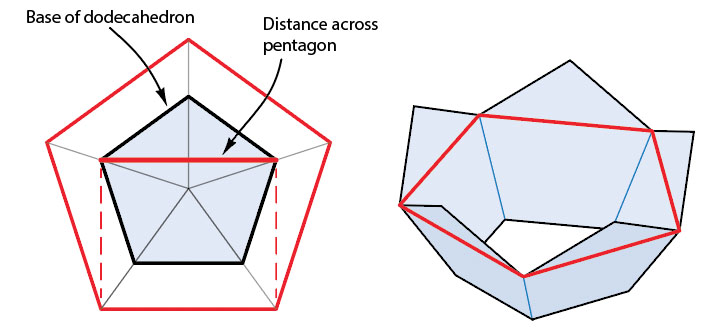

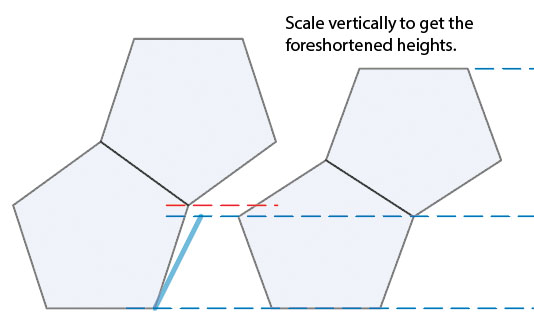

AxoTools is not a 3D application, but tries to assist illustrators in achieving a 3D look the best it can. Simple shapes are pretty straightforward, but complicated shapes can wind over and under each other like an

AxoTools is not a 3D application, but tries to assist illustrators in achieving a 3D look the best it can. Simple shapes are pretty straightforward, but complicated shapes can wind over and under each other like an

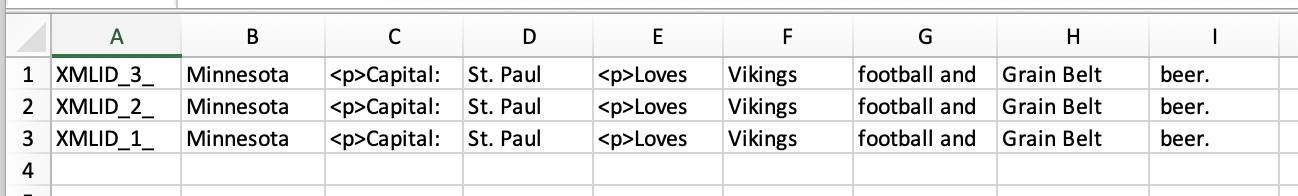

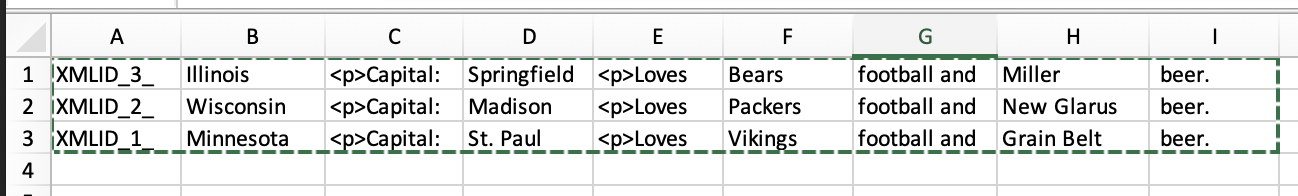

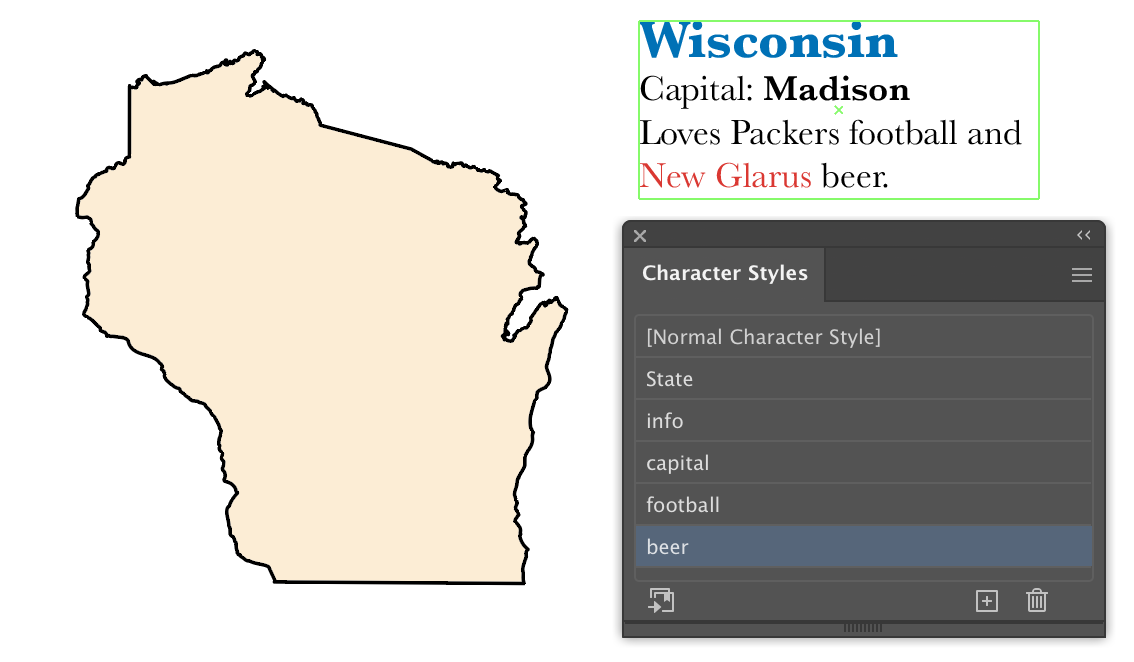

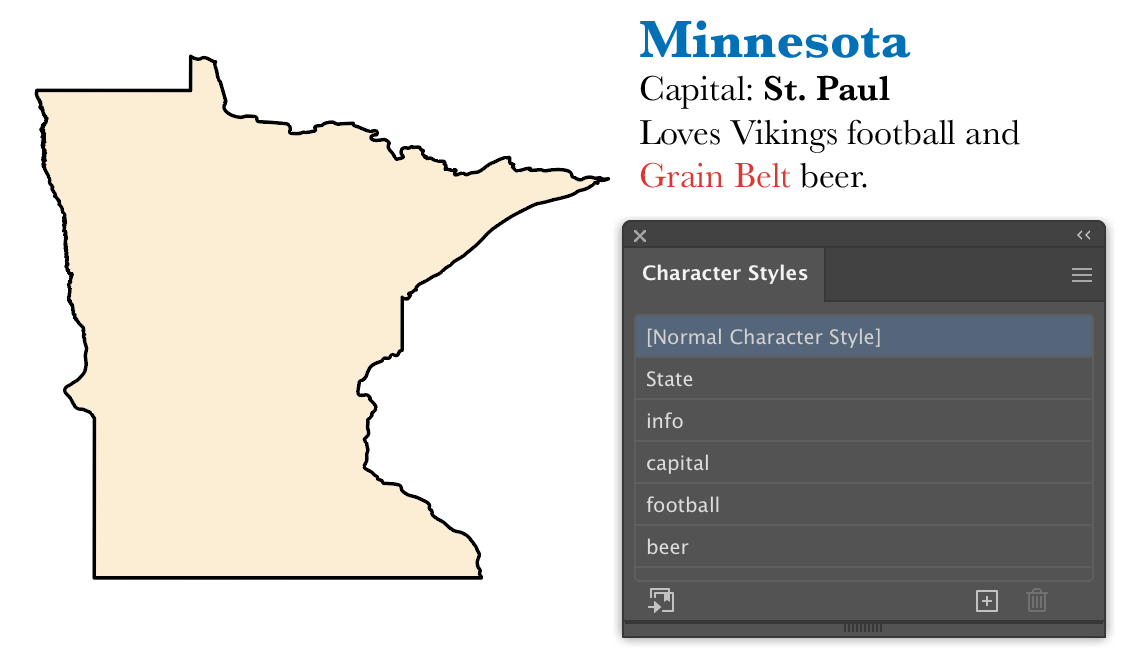

In this first example, we set the state name to a larger size, bold, and add a color. Assign a character style (I called it “State”). Assign the remaining text another style (in this case “info”). Select the capital city of St. Paul and change its formatting, then assign a style. Next, the term “Vikings” will change for other states, so select it and assign a new style, even though the actual formatting doesn’t change from the text surrounding it. Last, assign a character style to the text of the beer name.

In this first example, we set the state name to a larger size, bold, and add a color. Assign a character style (I called it “State”). Assign the remaining text another style (in this case “info”). Select the capital city of St. Paul and change its formatting, then assign a style. Next, the term “Vikings” will change for other states, so select it and assign a new style, even though the actual formatting doesn’t change from the text surrounding it. Last, assign a character style to the text of the beer name.